Tuesday, December 22, 2015

|

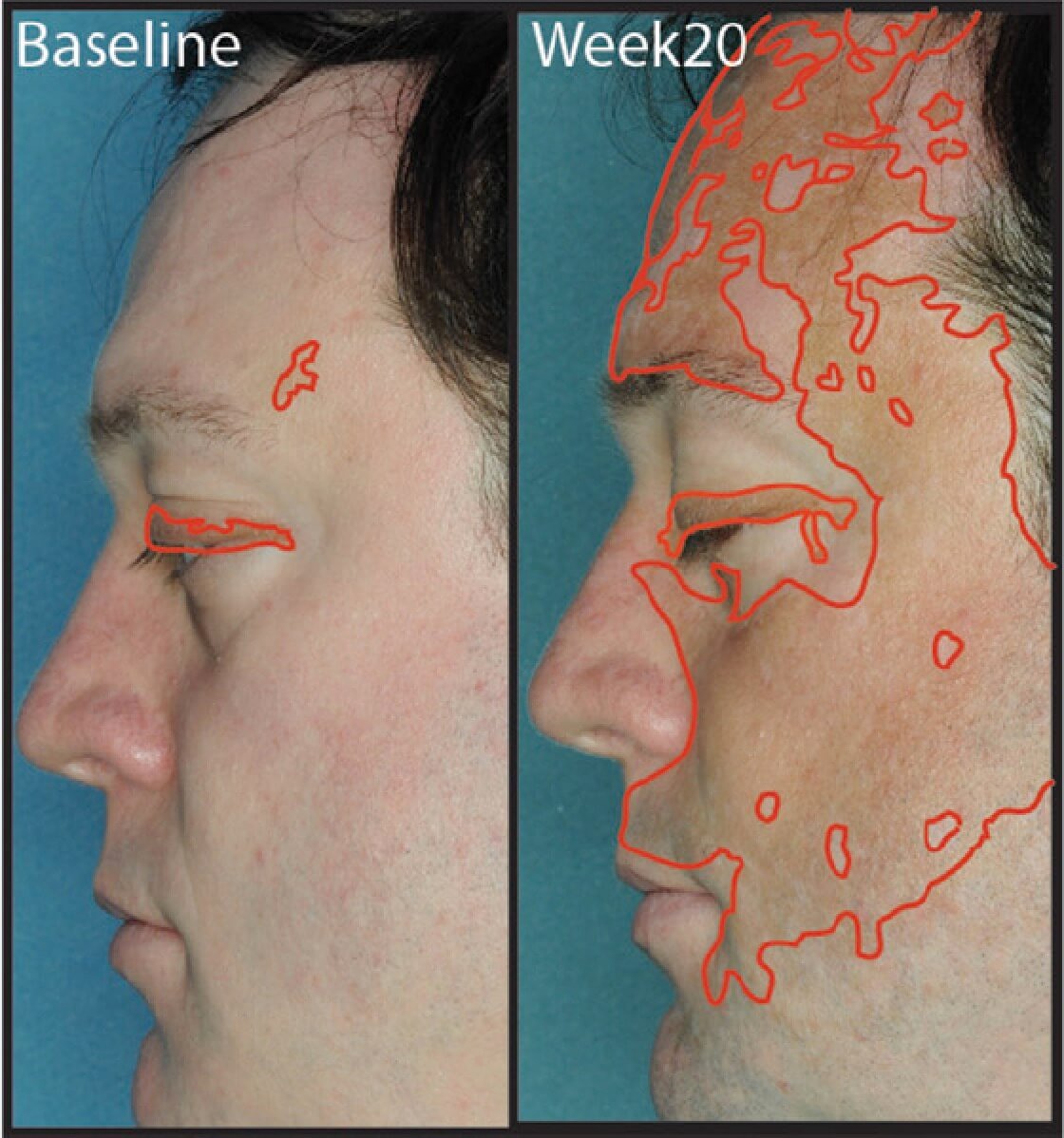

We recently published a report about a vitiligo patient who quickly improved after taking ruxolitinib (Jakafi), a drug that inhibits Janus Kinases (JAKs), which are important for signals that tell the immune cells where to go and what to do. Jakafi is FDA-approved to treat a subset of blood cancers, including myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera. This result is really exciting, because it is an oral drug that had a very rapid effect on vitiligo, improving the patient’s facial pigmentation from less than 1% to over 50% in just 4-5 months. We hypothesized that it might be effective because it blocks a pathway in the immune system that we have found to be critical for vitiligo. I just published an editorial summarizing our current understanding about how vitiligo works, and how we could develop new treatments for the disease that might be more effective, and also safer (you can download the PDF of our article here).

We recently published a report about a vitiligo patient who quickly improved after taking ruxolitinib (Jakafi), a drug that inhibits Janus Kinases (JAKs), which are important for signals that tell the immune cells where to go and what to do. Jakafi is FDA-approved to treat a subset of blood cancers, including myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera. This result is really exciting, because it is an oral drug that had a very rapid effect on vitiligo, improving the patient’s facial pigmentation from less than 1% to over 50% in just 4-5 months. We hypothesized that it might be effective because it blocks a pathway in the immune system that we have found to be critical for vitiligo. I just published an editorial summarizing our current understanding about how vitiligo works, and how we could develop new treatments for the disease that might be more effective, and also safer (you can download the PDF of our article here).

I previously wrote about a vitiligo patient who took tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and also had a significant improvement in her disease (read that here). It was a very popular post, generating lots of traffic and comments, which is a testament to the excitement in the vitiligo community about finding better treatments. This was an important observation made by Dr. Brett King at Yale because it was the first time a vitiligo patient reported a clear improvement in her disease from an oral drug, and the first time vitiligo had been treated with what we call targeted immunotherapy. That means that the drug affects the immune system (immunotherapy), but more importantly it does so without turning off the whole thing like steroids and other immunosuppressants, which have significant side effects. It targets just a small part of the immune system, in this case Janus Kinases (JAKs), which are important for signals that tell the immune cells where to go and what to do.

The potential advantage of targeted therapy is the ability to turn off just a small piece of the immune system, the piece that causes vitiligo, rather than the whole thing, which should leave other parts intact to fight infections. I am a big fan of analogies, so I’m going to use another one here. Imagine you are going to sleep and want to turn off the lamp next to your bed. You could do so by turning off the main circuit breaker to the house, but that would have lots of side effects, like turning off all of the lights in other rooms, alarm clocks, heat, etc. It would be better to turn off just the room switch, or even just the lamp. Like turning off just the lamp next to your bed, our goal is to find drugs that turn off only the part of the immune system that causes vitiligo, while sparing the parts that protect you from infections and cancer. That is not an easy task, which I explain here.

Now to clarify, Xeljanz still has broad effects, and maybe isn’t as targeted as we might like. It is considered a pan-JAK inhibitor, which means it blocks most of the proteins in the JAK family – it might be thought of as cutting the power to a few rooms in the house, since it affects multiple JAKs that are important for multiple immune pathways. Jakafi is probably a little more targeted, as it reportedly blocks mostly JAK1 and JAK2, which happen to be the specific ones required for vitiligo (via IFN-g signaling, read about that here if you’re interested). Jakafi also appeared to work in our patient the way we hypothesized it would, as shortly after treatment we saw a decrease of CXCL10 in the patient’s blood, an immune protein that gets turned on by JAK1 and JAK2 and is really important for vitiligo (read more about that here). So, when the patient took the drug, he improved and CXCL10 went down, supporting our hypothesis that it worked by turning off CXCL10.

But Jakafi still isn’t turning off just the lamp, maybe a couple of bedrooms. It does have some known side effects, like low blood counts, infections, and nonmelanoma skin cancers – you can read about the side effects of Jakafi here. Also, it wasn’t a durable treatment, meaning that when it was stopped, the patient’s vitiligo came back. This means that it might be a great way to rapidly stabilize and improve the disease, but it probably would have to either be continued to maintain its effect, or transitioned to another treatment for maintenance. So we’re still looking for more targeted treatments, but Xeljanz and Jakafi make a great start, representing at least a “proof of concept” that we’re on the right track, and that new treatments are just around the corner. Another thing to keep in mind is the cost of these drugs, which is very high – Jakafi is about $10,000 per month, primarily because it is a short-term treatment for cancer. But there appear to be “next-generation” drugs in the pipeline that may prove to be the key for vitiligo treatment in the future (again, see our editorial here). So stay hopeful, and stay tuned!