Kidney Cancer

The kidney is a bean-shaped organ located toward the back of the body, beneath the rib cage. A person is usually born with two kidneys, located on either side of our spine. The primary function of the kidney is to act as a filter to cleanse the blood of waste products and to make hormones to support blood pressure and blood cell production. The kidneys are composed of microscopic tubules that function as filtering units. As they filter the blood, the waste products accumulate into urine, which exits the kidneys via long tubes, the ureters, which pass into the bladder where the urine is stored and, eventually, expelled from the body.

Kidney cancer (also know as renal cell carcinoma) is an abnormal growth of the cells lining the tubules of the kidney. Cancers are formed when normal cells start to grow rapidly and without control. The body's normal defenses, formed by the immune system, are unable to destroy the cancer cells because they grow so quickly. As a result, these cells lump together and form a mass, known as a tumor or a cancer. Once a cancer begins to form, it can continue to grow uncontrollably and possibly spread beyond the area where it began. Microscopic pieces of tumor can also break off and spread to different locations of the body by way of the blood system or the lymphatic system. This spreading of tumor cells is called metastases. Metastatic spread is what makes cancer a deadly disease.

Renal Cell Carcinoma

Renal cell carcinoma is the medical name for the most common form of kidney cancer. Approximately 33,000 new patients with renal cell kidney cancer will be diagnosed in the United States this year. Many factors have been identified as potential causes of renal cell carcinoma. These include: cigarette smoking, which doubles the risk and contributes to as many as one-third of the cases; obesity; high blood pressure and high blood pressure-related medications; occupational exposure to petroleum products, heavy metals, or asbestos; and hormonal imbalances.

Traditionally, many patients with kidney cancer found out about their disease because of seeing blood in the urine, noticing a mass in the side of their body, or because of side (flank) pain. Unfortunately, kidney cancer does not always reveal its presence in these ways and many kidney cancers remain undetected until they become very large simply because there are no signs or symptoms that specifically point to its diagnosis. Currently, there are no laboratory tests available to specifically detect kidney cancer. However, some warning signs can alert you to the possibility of a kidney cancer. These include: blood in the urine (even under the microscope), discomfort in the side or back that will not go away, feeling tired, lose their appetite, experiencing weight loss without dieting, having abnormal blood counts. Many patients never experience any symptoms and cancer is diagnosed when they are examined or tested for an unrelated complaint or at a regular doctor’s visit. Such “incidental” findings are how most kidney tumors are discovered.

Most of the tests a doctor will order to determine if you do indeed have renal cell carcinoma are radiological studies. An ultrasound study is a common initial study: it takes a picture of kidney that can be seen on a television screen. Ultrasound is a very sensitive technique to differentiate solid tumors from liquid tumors (cysts). The diagnosis of kidney cancer often requires a CT scan or an MRI scan. These are sophisticated imaging studies that image the organs of the body very closely and are considered the best test for determining the presence of masses on the kidney. MRI can also be used to check for the presence of tumor in the blood vessels of the kidneys. A bone scan may be ordered to determine whether the kidney cancer has spread to the bones. A renal scan can help determine how well the kidneys are functioning. Blood tests can be performed to look for abnormal levels of creatinine, a sign of impaired kidney functioning, or abnormal levels of liver enzymes, which may suggest that the cancer involves the liver.

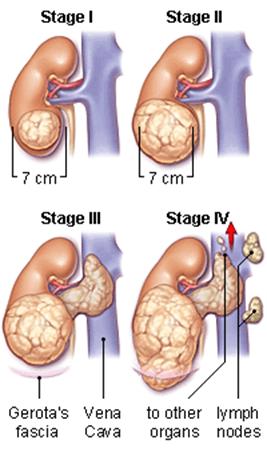

“Staging” refers to the process of determining how much cancer is present in the body and where it exists. All cancers are assigned a “stage” prior to treatment. Such staging is important because it helps to determine the prognosis as well as the type of treatment that would be most beneficial. The stage of the cancer is simply a means of defining the extent of the tumor: whether the cancer is only in the kidney, or whether it has spread to other places in the body. In order to stage a cancer, several diagnostic tests may be obtained: imaging of the abdomen, pelvis, chest, and, perhaps, the head. There might be a chest X-ray, bone scan, and/or blood tests.

Stages of renal cell carcinoma:

◦ Stage I: Cancer is in the kidney only and the size of the tumor is less than or equal to 7.0 cm in diameter.

◦ Stage II: Cancer is in the kidney only but the size of the tumor is greater than 7.0 cm in diameter.

◦ Stage III: The tumor in the kidney may be any size, but it extends beyond the layer of tissue (Gerota's fascia) that encapsulates the kidney and adrenal gland. Additionally, cancer may have spread to blood vessels that carry blood away from the kidney, or to the adjacent adrenal gland.

◦ Stage IV: Tumor in the kidney extends beyond Gerota's fascia and/or cancer has spread to one or more lymph node near the kidney. In addition, there may be evidence that cancer has spread to other organs in the body, such as the lungs, liver, brain, or bones.

The stage of the cancer, as well as the age and general health of the patient, help to determine what treatment will be most effective. Surgery is usually indicated for the treatment of kidney cancer. Surgery consists of either a radical nephrectomy, which involves removing the whole kidney and the tissues that surround it, or a partial nephrectomy (nephron-sparing surgery), where only the area of the kidney that contains the tumor is removed. In general, a radical nephrectomy will not generally endanger the body's ability to filter waste products if the patient has a normal opposite kidney: many people can live healthy lives with only one kidney. Still, whenever feasible, a partial nephrectomy is preferred as it will provide a patient with the greatest amount of normal kidney function after surgery.

Both open and minimally-invasive (robotic-assisted laparoscopic and/or laparoscopic) surgical techniques are used to perform kidney surgery. Laparoscopic and robotic surgery are minimally invasive techniques in which the surgeon views the anatomy and performs the operation using a camera and tools inserted through small holes in the patient's skin. Minimally-invasive approaches are preferred due to the accelerated recovery they offer. The adrenal gland, which sits above the kidney, may or may not be removed, depending on the individual situation. Lymph nodes surrounding the kidney may or may not be removed, depending on the individual situation. These issues are best left to a discussion between the patient and his or her surgeon.

Surgical Treatment Options for Kidney Cancer

Most solid kidney tumors are discovered incidentally – meaning that they are found by chance during radiologic studies obtained during the work-up of an unrelated medical condition. Most of these kidney tumors are cancerous. Fortunately, many can be cured with surgery. Some kidney tumors are not cancerous and cysts (fluid-filled tumors) can be either cancerous or benign. The relative risk that a given kidney mass is a cancer is based primarily on radiologic features (such as solid or cystic components; irregularity of shape, and the presence of fat). Still, most “solid, contrast-enhancing masses” or “complex cystic lesions” (in the medical lexicon) are cancerous and generally require removal.

A wide range of therapeutic options are available for treating renal cell carcinoma. These include: radical nephrectomy (removing the entire kidney), and partial nephrectomy (removing just the cancerous part of the kidney). In addition, some lesions may not require treatment and can be followed with imaging studies (active surveillance) and several drug treatments that can be used in combination with, or instead of surgery, depending on the size and extent of the tumor.

Radical Nephrectomy

This involves removal of the entire kidney, the adjoining adrenal gland, and the surrounding fatty tissue (all contained within Gerota’s Fascia). This operation is commonly used for large renal cell carcinomas that are not amenable to partial nephrectomy. Radical nephrectomies can be performed in either an open or laparoscopic (minimally-invasive) manner. Recovery after laparoscopic surgery is quicker and, hence, is the preferred technique whenever possible.

◦ If the tumor invades surrounding organs (such as the liver or spleen) or is involving the inferior vena cava, these structures may be removed in addition to the kidney. Depending upon the location and extent of such locally-advanced disease, open or laparoscopic techniques may be used.

◦ Often this operation is combined with a lymph node dissection.

◦ Larger kidney tumors may recur even after complete surgical removal. Therefore, anti-cancer drugs (systemic medical therapy) may be given after surgery to help prevent recurrence.

Partial Nephrectomy

Partial nephrectomy is also known as nephron-sparingsurgery. This involves removal of just the tumor, leaving the surrounding normal kidney tissue intact. This operation is the preferred approach to kidney cancer surgery and is crucial if a patient has or is at risk for kidney failure (such as severe high blood pressure, kidney stones, diabetes). It is also used for patients who have one kidney or tumors in both of their kidneys.

◦ Partial nephrectomies can be performed in an open or robotic-assisted laparoscopic, or laparoscopic (minimally-invasive) manner. Recovery after laparoscopic surgery is quicker and, hence, is the preferred technique whenever possible.

◦ Partial nephrectomy is a more complicated operation than removing the entire kidney and a patient who is a potential candidate for nephron-sparing surgery should consider being evaluated at an academic medical center that performs a high volume of partial nephrectomies, such as the fellowship-trained urologic oncologic surgeons in the UMass Department of Urology.

Transitional Cell Cancer

A second type of kidney cancer is called transitional cell cancer. This type of cancer is very similar to bladder cancer and can involve the kidney or the ureters, the tubes that empty the kidney and drain urine to the bladder. These cancers are relatively rare, affecting approximately 4,000 people in the United States each year. There is a strong association with smoking exposure and employment in the chemical and petroleum industries. It is important in these patients to evaluate the bladder for the presence of cancer, as concomitant disease is common. Hence, most patients with transitional cell cancer of the upper tract (kidneys or ureters) will also undergo cystoscopy, an examination of the bladder with a small telescopic instrument.

The extent of the cancer, as well as the age and general health of the patient, help to determine what treatment will be most effective for transitional cell cancer. The most likely initial treatment will be surgical. Surgery almost always involves a nephroureterectomy, which involves removing the entire kidney and ureter, the tissues that surround them, and a small “cuff” of the bladder where the ureter inserts.

If the tumor is limited to a small section of the ureter, the patient may be a candidate for a ureterectomy. This operation involves removing the segment of ureter containing cancer and then reconnecting the two ends, leaving the kidney in place. The appropriateness of this operation depends upon the aggressiveness, location, and extent of the cancer and the standard of care remains the nephroureterectomy (removing the entire kidney, ureter, and “cuff” of bladder). In very select cases, a patient may undergo endoscopic surgery, in which the tumor is removed while the kidney and ureter are left intact. This is rarely performed and is usually reserved for patients with poor health, poor kidney function, and very small, very superficial, and very non-aggressive tumors.

Nephroureterectomy

◦ This involves removal of the kidney, the ureter, and cuff of bladder and all of the surrounding tissue.

◦ Nephroureterectomy can be performed in an open, laparoscopic (minimally-invasive), or robotic-assisted laparoscopic manner.

◦ Nephroureterectomy may be combined with removal of the regional lymph nodes and, rarely, removal of the bladder (a cystectomy).

◦ A ureterectomy involves removal of all or part of the ureter, leaving the kidney intact. Ureterectomies can be performed in an open or laparoscopic (minimally-invasive) manner.

◦ Endoscopic surgery involves removing a transitional cell cancer of the kidney or ureter through a telescope inserted through the urethra and into the bladder. This operation is not commonly performed.

◦ If the cancer has spread to tissue surrounding the kidney or ureter, or if it has metastasized to distant organs (such as the lung or liver), drug therapy (chemotherapy) may be used in addition to surgery.

Other Kidney Cancers

There are other tumors that can affect the kidney. Renal sarcomas are treated similarly to renal cell carcinoma, but often require the addition of chemotherapy. Angiomyolipomas (a tumor consisting of fat, muscle, and blood vessels) can be treated in a variety of ways: including surgery, embolization (blocking the blood supply to the tumor) and observation. Lymphomas are treated with drug therapies. Oncocytomas are benign lesions that resemble renal cell carcinomas and the diagnosis is often made after surgery.