Trusted health care providers could increase vaccine acceptance among the 40 percent of Americans who say they are hesitant or not likely to get a COVID-19 shot. Researchers at UMass Medical School are working to identify what message doctors should convey to their patients to be most effective.

Kimberly Fisher, MD, associate professor of medicine, and Kathleen Mazor, EdD, professor of medicine and associate director of the Meyers Primary Care Institute, have been tracking vaccine acceptance since April 2020. They conducted an online survey in January of more than 1,700 adults, measuring the impact of different messages from health care providers encouraging those who were hesitant to become more willing to be vaccinated.

The survey also explored what information people base their decisions on, particularly among vulnerable populations, who were oversampled in this latest study.

They found that COVID-19 vaccine-hesitant individuals became less hesitant after a brief recommendation from a doctor.

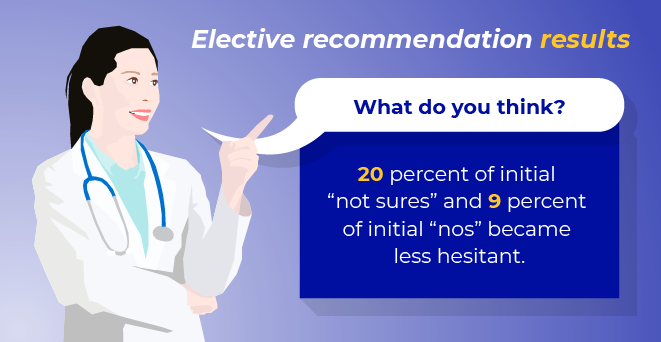

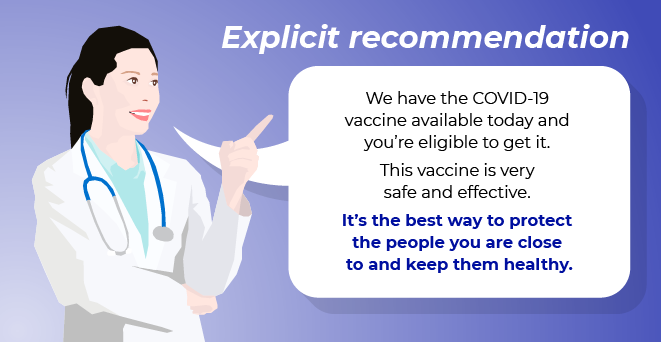

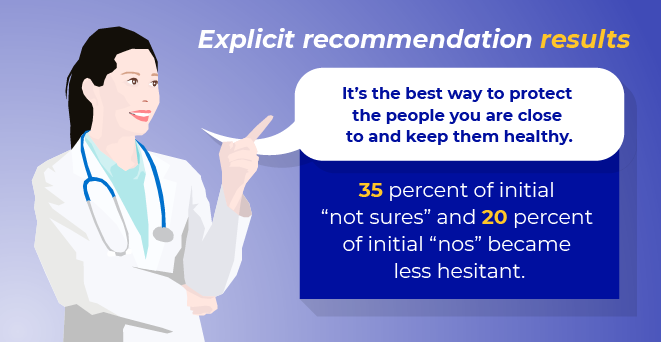

An explicit recommendation to get vaccinated was more effective than a general offer from a provider to administer the vaccine. Further, among those initially most resistant, a message that emphasizes getting the vaccine to protect others was found to be most influential in reducing hesitancy.

Researchers also found that survey respondents who were classified as vaccine hesitant were less likely to rely on numbers and statistics when they make decisions, and they had less accurate knowledge of COVID-19 and COVID vaccines.

“In our mind, the question is, what do people rely on, if not numbers and statistics? Is it the doctor’s advice? How can we leverage those things?” asked Dr. Mazor.

Dr. Fisher added, “So, why does the recommendation from somebody you trust influence you? I think a lot of people make decisions with shortcuts. And they don’t want to have to say, ‘Let me do the research myself and decide if I should get this vaccine.’”

The survey, conducted with support from the Network of the National Library of Medicine New England Region, based at Lamar Soutter Library at the Medical School, asked participants whether they intended to be (or had been) vaccinated against COVID-19.

Nearly one out of four said no and another one out of five said they weren’t sure. Slightly more than half said yes, or they had already been vaccinated.

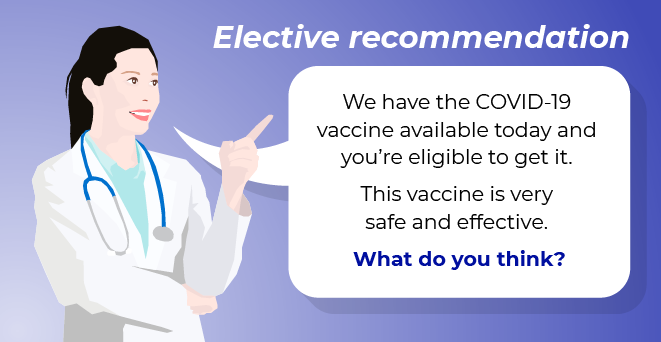

The 44 percent who initially responded “no” or “not sure” were randomly assigned to receive one of five messages from their health care provider during an imagined office visit. All messages began with, “We have the COVID-19 vaccine available today and you’re eligible to get it. This vaccine is very safe and effective.”

After reading one of five varied messages that followed, participants were again asked whether they would get vaccinated at that visit.

About one-third of those who were initially not sure later said they would accept the vaccine following a physician’s recommendation. A smaller portion, approximately 12 percent of those who initially said no to the vaccine, changed their position to “not sure” or “yes.”

The researchers are preparing to follow up with those who were initially hesitant in January, to see if they have received the vaccine and to probe some more about what affected their decision.

“There have been repeated surveys, but they don’t necessarily go back to the same group. This will be unique in going back to the same exact people whom we’ve characterized in January and seeing what’s happening to them over time,” Fisher said. “We’re really eager to learn from them what changed their mind.”

Fisher is the principal investigator on a new, $2.2 million, three-year grant from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to conduct a pragmatic trial of how primary care providers’ recommendations to get the COVID-19 vaccine work in actual primary care settings.

Primary care clinics serving vulnerable minority and socioeconomic groups in Worcester will be randomly assigned to either have their unvaccinated patients receive text messages from their provider, encouraging them to get the vaccine and link to other resources and scheduling help; or to provide care as usual, as a control group. Providers in the clinics assigned to the intervention will also receive information about making a strong recommendation rather than an open-ended, elective one.

“The next step is to basically develop a system whereby health care providers can make these recommendations en masse and outside a visit, because the vaccines aren’t currently being given from doctors’ offices and not everyone has an appointment with their doctor,” Fisher said.

Related stories on UMassMed News:

Researchers to study health care providers’ influence on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance

UMMS researchers study attitudes toward potential COVID-19 vaccine