Three genes, double trouble for nicotine addiction and lung disease

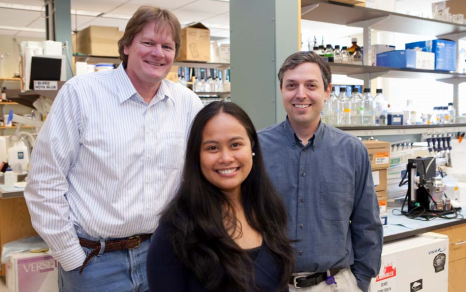

There is a clever saying that’s sometimes used to sum up human predisposition to disease: “Genetics loads the gun and environment pulls the trigger.” Paul D. Gardner, PhD, associate professor of psychiatry, Andrew R. Tapper, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry, and GSBS student Reina Improgo, have identified a trio of genes that not only load the gun, they put a finger on the trigger when it comes to the relationship between nicotine addiction and lung disease.

Working in the Gardner/Tapper laboratory in the Brudnick Neuropsychiatric Research Institute, the group is studying three genes—CHRNA5, CHRNA3 and CHRNB4—that produce a specific type of nicotine receptor that not only increases a person’s likelihood of developing nicotine addiction, but also increases a person’s risk for developing lung cancer. The research team discovered that the genes are expressed in small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC)—the most aggressive form of lung cancer—at levels dramatically higher than those seen in normal lung tissue.

“The impact of nicotine addiction and lung cancer on global health is undeniable,” says Dr. Gardner, whose own father dealt with health issues related to his two-packs-a-day habit. More than 5 million deaths per year are attributed to cigarette smoking, and lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths around the world. (Although breast and prostate cancer are more prevalent, lung cancer is more deadly; only 14 percent of lung cancer patients survive after five years.) More than 95 percent of patients with SCLC have a history of smoking cigarettes.

The team’s findings, published in February in Molecular Cancer Research support the hypothesis that nicotine receptors play a role in lung cancer distinct from their role in nicotine addiction. Based on these results, the team is now testing the hypothesis that silencing the genes will affect the growth of tumor cells. Preliminary data indicate that silencing the genes does lead to decreased growth of the cells. The team is investigating the effect of nicotine exposure on the growth of lung tumors as well as the effect of drugs that target the three genes. In particular, they are testing the effect of a specific snail toxin, one that blocks the function of nicotine receptors, in the pathogenesis of lung cancer.

“This is promising because there is already considerable research into the development of drugs targeting nicotine receptors, in part because of the role these receptors play in several neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and schizophrenia,” said Improgo. “Our discovery that CHRNA5/A3/B4 is important in lung cancer and not just in nicotine addiction provides another compelling reason for continued efforts in this area.”

Improgo was invited to present the work as a “Hot Topic” at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience in San Diego in November, a conference expected to attract more than 30,000 members.