Everything that lives produces waste. This is true even for cancer cells. Scientists from UMass Chan Medical School have found a way to poison cancer cells with their own waste.

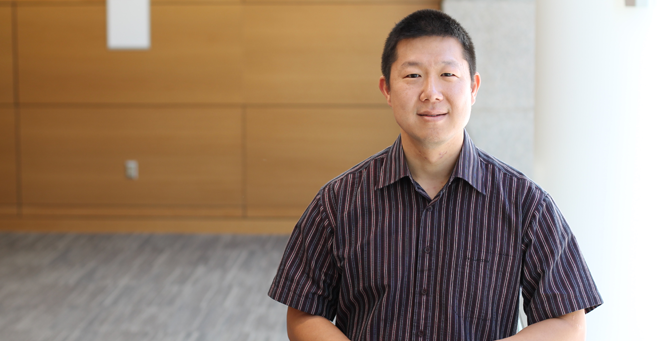

Published in the journal Nature, a new paper by Dohoon Kim, PhD, and colleagues shows that blocking the detoxifying enzyme UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase 1 (UXS1) in lung cancer cells leads to cell death, making it a viable target for drug development.

In the process of metabolism, cells create or break down various metabolites with enzymes to produce energy, grow and carry out tasks. Some of these metabolites, however, are toxic and can potentially be hazardous at higher levels. To compensate, cells produce specific enzymes that detoxify certain metabolites, neutralizing the waste before it can build up in the cell.

“Depriving cancer cells of nutrients and starving them is a well-studied approach to treating cancer,” said Dr. Kim, associate professor of molecular, cell & cancer biology. “We are exploring the other side of this coin—identifying what accumulates when you remove an enzyme responsible for detoxifying these toxic metabolites—the objective being to find a way to make the cancer cells poison themselves.”

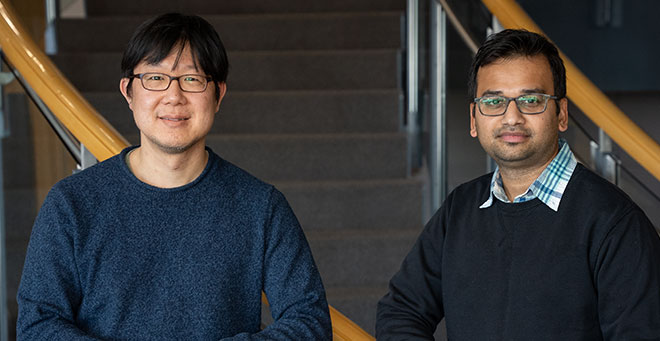

Mining publicly available data sets on cancer cell metabolites and enzymes, Mihir Doshi, PhD, postdoctoral associate and first author of the Nature study, began looking for dependent relationships between enzymes. “Our hypothesis was that if we could find an enzyme that only becomes important when the enzyme immediately upstream of it is active, then the downstream enzyme might be required to remove the toxic product of the upstream enzyme.”

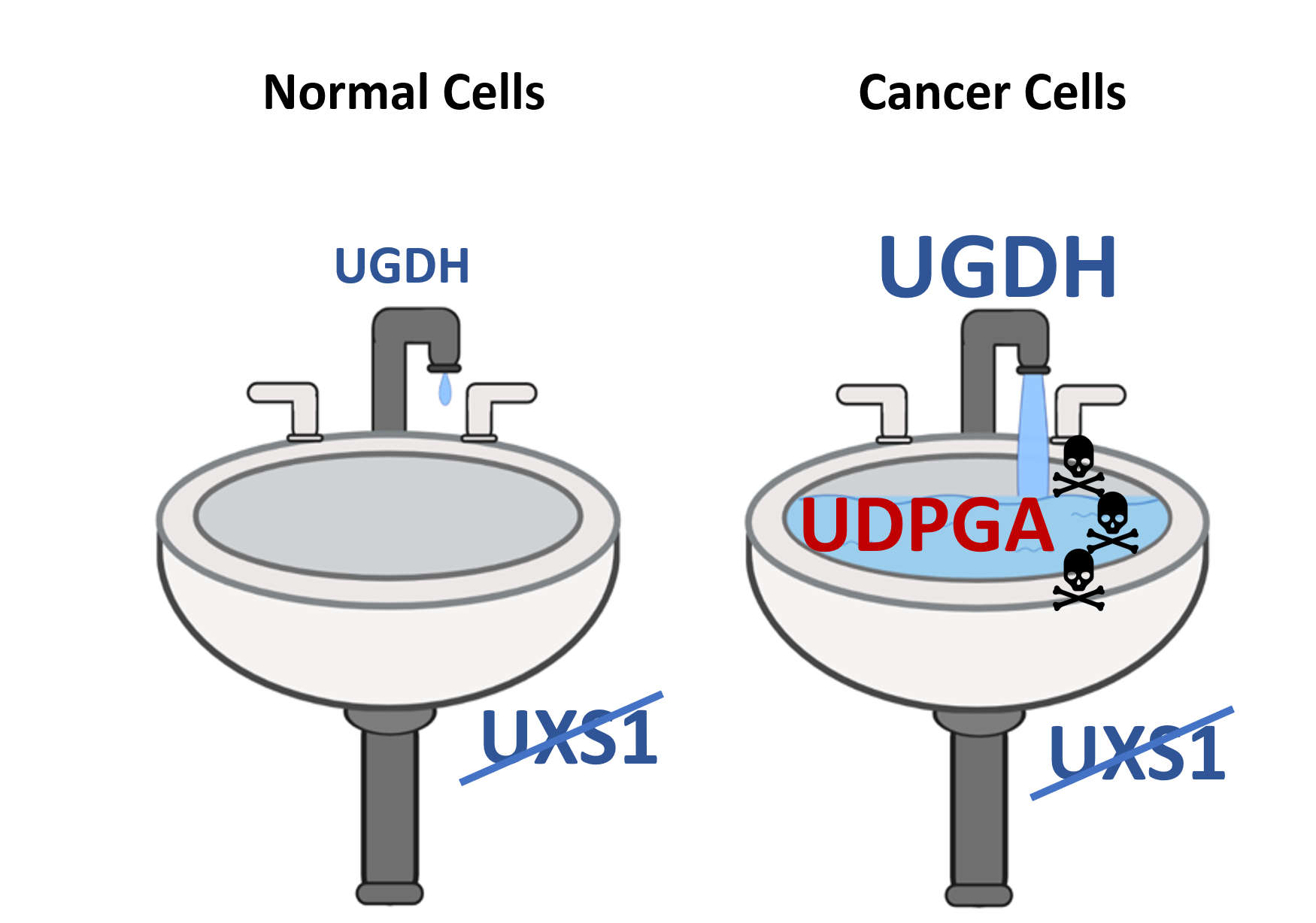

Using this approach, Dr. Doshi and the Kim lab found that lung cancer cells expressed an abnormally high level of the enzyme UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase (UGDH). In conjunction with the increased UGDH, lung cancer cells also expressed high levels of the enzyme UXS1. Experiments confirmed that the UGDH enzyme in lung cancer cells was producing high rates of the metabolite UDP-glucuronic acid (UGPDA) and it was the job of the UXSI enzyme to clear out this toxic metabolite. When Kim and Doshi knocked out the UXSI enzyme, the lung cancer cells were no longer able to remove the toxic UGPDA metabolic. The resulting build-up eventually caused the lung cancer cells to die.

“It’s like clogging a drain,” said Kim. “The faucet is the upstream metabolic enzyme (UGDH) producing the toxic metabolite (UGPDA), and the drain is the detoxifying enzyme (UXSI). In cancer cells, the faucet is gushing toxic levels of metabolites, but in healthy noncancer cells, the faucet is barely dripping. By inhibiting the detoxifying enzyme, we’re clogging the pipes that drain the toxic metabolite, allowing the metabolite to accumulate to dangerous levels in cancer cells. But because the faucet is barely on in normal cells, they remain unaffected, and healthy.”

Because UGDH is highly expressed in many chemo-resistant lung cancers, it is a good target for drug development as it may be effective against chemoresistant cancer cells and treatment-resistant tumors. UGDH can also serve as a biopsy biomarker to identify patients who might benefit from a drug-blocking UDPGA neutralization.

Dr. Kim received funding from the BRIDGE Innovation and Business Development Office’s Bridge Fund to pursue the next phase of investigations.