New ways to accelerate antibiotic development are urgently needed as superbugs multiply, according to Celia A. Schiffer, PhD, professor of biochemistry & molecular pharmacology and co-director of the UMass Institute for Drug Resistance.

“The time is definitely now for this discussion,” Dr. Schiffer said. “This is a huge problem and we need action. The pipeline for new antibiotics is almost non-existent, largely because it has become unprofitable.”

President Obama has just announced a plan to invest tens of millions of dollars in antibiotic development, set up a new antibiotic research network and loosen up the approval process for new drugs tackling resistant strains. That last proposal is the most contentious, with some critics worrying it amounts to cutting corners.

“We certainly don’t want to inadvertently encourage more resistance, but we definitely have smarter ways to design antibiotics now, and probably smarter ways to use the ones we have, too,” Schiffer said.

The UMass Institute for Drug Resistance is a consortium that works on a spectrum of issues related to drug resistance. A key part of that work involves determining exactly how resistance arises and how it can be avoided.

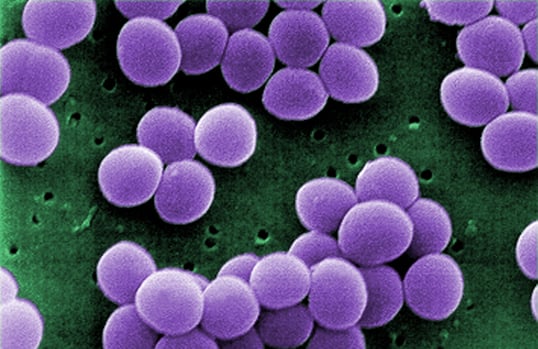

“Bacteria have a natural ability to evolve defenses,” Schiffer explained. Another problem is the widespread misuse and overuse of antibiotics, especially in agriculture. Chickens, cows and other livestock have long been fed antibiotics not because they are sick, but because it fattens them up. This is the sort of overuse that leads the rapid evolution of antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria.

Community- and hospital-acquired drug-resistant infections are increasing at an alarming rate. In 2011, the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health made headlines when almost 20 patients contracted a drug resistant infection, several of whom died. More recently, a drug-resistant “superbug” infected at least one patient in each of nearly 200 US hospitals and long-term care facilities during just the first six months of 2012. The superbug is resistant even to the antibiotic of last resort held aside for such cases.

With such high demand for antibiotics, it seems like pharmaceutical companies should be racing to develop new antibiotics, but these drugs are not very profitable. They are prescribed for much shorter periods of time than those in the blockbuster categories of chronic diseases, such as asthma, heart disease and diabetes. Antibiotic use can also be quickly curtailed by widespread resistance.

“Even when antibiotics with novel mechanisms are developed, the FDA often wants to keep them on hold so they are available when the next superbug comes along,” said Schiffer.

It is also hard to gather sufficient data for FDA approval, because the window for testing new antibiotics in patients with resistant infections is very narrow. “If a patient is failing antibiotics,” Schiffer said, “They probably have even less time to try a new treatment than a cancer patient who is failing a chemotherapy.”

Streamlining the approval process and making it more financially rewarding might get more companies involved. At the moment, most of the major drug manufacturers have dropped out of antibiotic development. “But some smaller companies, in particular, are coming up with novel types of antibiotics that may not encourage resistance as quickly,” Schiffer said.

It’s difficult work, because bacteria are well equipped to defend themselves. Some can keep drugs from penetrating their outer membrane, others can pump drugs that do get in right back out. And some bacteria have enzymes that chop up the drugs before they can work. Bacteria also have a way of sharing their genes with each other so they can swap resistance mechanisms. The UMass Institute for Drug Resistance was created to study just such problems.

Related Links on UMass Med Now:

Expert’s Corner: Celia Schiffer, PhD, on drug resistance

Institute for Drug Resistance hosts workshop